Following the recent shocking report from the NDDB CALF laboratory, which revealed that beef tallow was used in making ladoos at the Tirupati Tirumala Mandir. This temple, known for supplying ladoos across India, even provided them during the consecration of the historic Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. The report sparked mass outrage within the Hindu community and reignited an age-old debate spanning centuries: the issue of temples under state control.

In 1817, the Madras Regulation was enacted, which allowed the East India Company (EIC) Board of Revenue to also take over all "endowments" associated with religious buildings on the pretext of reducing the amount of charity and assets that were allegedly embezzled by pundits and religious icons. Endowments referring to all financial assets of a religious structure, including land, donations, and even the idol of the deity itself. This brought thousands of Hindu temples, as well as Mosques under direct EIC control, making the British the sole proprietors of all religious institutions in the areas they controlled.

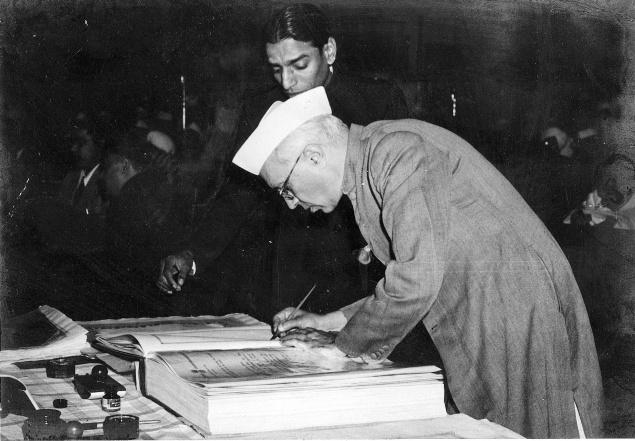

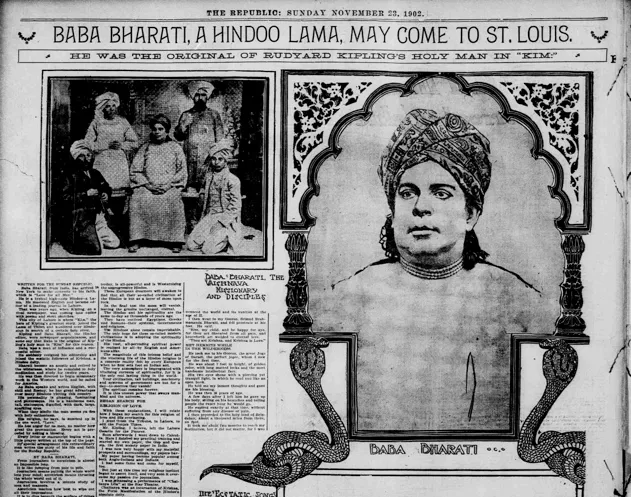

Religious interference by the EIC continued, until the Revolt of 1857 after beef and pork fat was used in cartridges used by the Indian Forces for the Company. After Company territories were consolidated as part of the British Empire, the Religious Endowments Act of 1863 was brought, which relieved the Board of Revenues of their duties and allowed private entities to once again own all religious endowments. Thanks to the revolt, government control in religious matters was kept to a minimum until 1923.

Going further back, Hindus faced similar ordeals under Mughal rule, through the imposition of Jizya. Which was the price for Mughal tolerance of Hindus. Emperors like Akbar were reportedly known to abolish this practice to ensure equality for all people regardless of religion. However, rulers like Aurangzeb implemented these draconian laws in their dominions as an effort to marginalize the native Hindu community of mainland India.

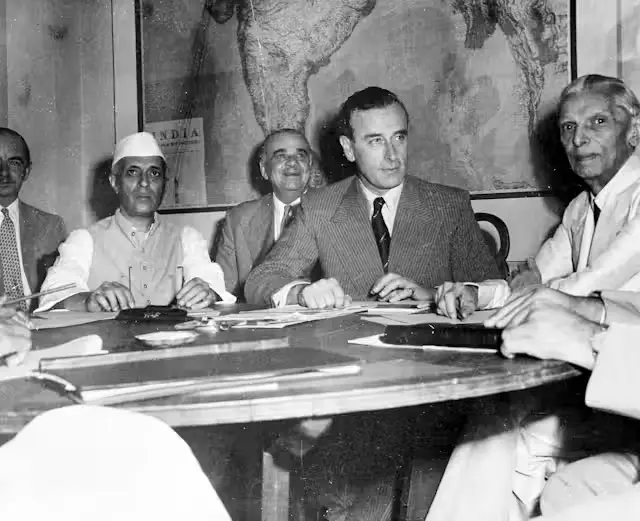

However, as citizens of independent India, and not part of theocratic and religiously driven empires, one might expect these laws to no longer hold weight. Yet, the independent India Hindu Religious Endowments Act was pioneered by Tamil Nadu through the TN Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act, 1959 as highlighted by Supreme Court Lawyer and Activist J. Sai Deepak, in his book "India that is Bharat”. The Act explicitly mentions - Hindu temple endowments, excluding Jain, Sikh, and Buddhist structures, be immediately transferred to the State government. It grants the state government significant control over temple administration, including appointing executive officers, managing finances, properties, and overseeing the appointment of priests and other staff.

Following the Tamil Nadu footsteps, states like Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka also grant exclusive control of vast, rich Hindu temples to the secular State government – often headed by non-Hindus and non-religious persons. There are numerous sacred, and massive Hindu temples in Southern India, generating annual revenues in the hundreds of crores. For instance, the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai collects over 60 crores worth of cash, gold, and diamonds annually. Temples in Karnataka generated a total revenue of ₹744.29 crore, with the top 205 'A' category temples alone contributing ₹709.32 crore. The Tirumala Tirupati Venkateswara Temple, one of the richest in India, has an annual income of approximately ₹1,450 - ₹1,613 crore.

Reports of misuse of temple funds by the State are not uncommon. In Karnataka, it was reported that in 1997, out of ₹52 crore collected from 264,000 Hindu temples, only ₹17 crore was returned for maintenance. ₹12 crore was allegedly diverted to support madrasas and churches, while the remaining ₹23 crore was used by the government for its own programs.

In Tamil Nadu, allegations suggest that temple funds are being misused for public infrastructure projects. For example, ₹8.5 crore was allocated for constructing a road to the Tirutani Murugan temple, which activists argue should be handled by the Highways Department, not using temple funds.

In Andhra Pradesh, it's alleged that only 22% of the revenue from about 34,000 temples controlled by the state government is given back for temple maintenance and management, while the remaining 78% is used for other purposes.

It doesn’t end here unfortunately; the new bill passed by the Karnataka government, called the "Karnataka Hindu Religious Institutions and Charitable Endowments Bill 2024," mandates that temples earning over ₹1 crore annually must contribute 10% of their income to a Common Pool Fund (CPF), while those earning between ₹10 lakh and ₹1 crore must contribute 5%.

This raises the question: What right does a secular state government have over the revenue generated and charity given towards strictly religious institutions? Or are the temples themselves nothing but extensions of the executive branch of the Secular government, giving them the sole right to control how, why, and what people worship? In this context, beef tallow ladoos don't seem too far-fetched or extraordinary, it was just a matter of time. Something to note however, there are no equivalent laws for mosques or churches. These institutions are owned and operated by their respective religious organizations without government interference. The government does not charge mosques or churches fees similar to those imposed on Hindu temples. In some cases, mosques and churches even receive monetary support and other benefits from the government.

The question we must ask ourselves, what right does the government have to control said places of worship, that violates the secular nature of this country and constitution. People donate to these institutions with the impression their money would be put to use to further their devotion, and not fill the pockets of some MLA, or Member of Parliament.