In this except from his new book Shattered Lands, Sam Dalrymple reveals the turbulent personal and political life of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the man who would oversee the Partition of India. Through sharp prose and narration, Dalrymple captures the contradictions of a collapsing empire: aristocratic excess concealing a lack of competence, personal scandals and global decision-making, as well as colonial theatre clashing with ground realities. Dalrymple provides a window into the twilight of British rule, as seen through the lens of one of its most theatrical protagonists

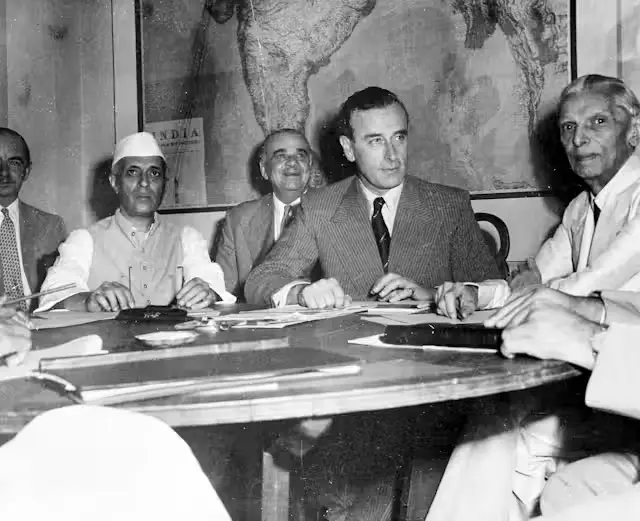

To head South East Asian Command (SEAC), Churchill appointed a famously charming naval officer whose penchant for pomp and cere- mony would loom large over the subcontinent in years to come. Lord Louis ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten was a cousin of the king and a relative of virtually every royal in Europe. Four years later he would oversee another, even greater Partition of India, on the basis of religion rather than race.

It was not Mountbatten’s first trip to the subcontinent. In 1921–2 he had accompanied the Prince of Wales on a four-month tour, beginning in Aden where a huge banner greeted them with the words ‘Tell Daddy We Are All Happy Under British Rule’ – an amiable start to a rather tense trip. Gandhi had announced mass protests to the royal visit, and Mountbatten was fated to travel across a riot-stricken land- scape. ‘I need you so badly,’ wrote the lovesick lord to his girlfriend Edwina as he toured across India, and so she decided to join him. She was one of London’s wealthiest women, descended from both the British prime minister Palmerston and Pocahontas, yet her youth had been an unhappy one, complete with a wicked stepmother and board- ing school bullies who ridiculed her for her Jewish German heritage.

India provided Edwina with an escape beyond her wildest imagination and she fell in love with it instantly. She met up with Mountbatten shortly before the Valentine’s Day dance at the Viceregal Lodge. ‘I danced 1 and 2 with Edwina,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘She had 3 and 4 with David, and the 5th dance we sat out in her sitting-room, when I asked if she would marry me and she said she would.’

The glamorous socialites returned to the UK the next month and were married in St Margaret’s Church, Westminster. On their honey- moon they were hosted by Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood but nonetheless their marital bliss was short-lived. Edwina came to detest Mountbatten’s long absences in the navy and embarked on a long series of affairs, while he grew deeply jealous of her infidelities, particu- larly when they crossed the racial line. When she started sleeping with the black cabaret star Leslie Hutchinson, band member Alfred Van Straten recalls Mountbatten approaching him in a drunken stupor and mumbling, ‘I am lonely and drunk and sad.’ Pulling out a seat opposite, he spat, ‘That n*gger Hutch has a prick like a tree trunk and he’s fuck- ing my wife right now.’

By the end of the decade, the marriage had effectively become an open relationship, and he had started an affair of his own with the French socialite Yola Letellier (and possibly a slew of men as well). ‘Edwina and I spent all our lives getting into other people’s beds,’ Mountbatten later recalled. But unlike Edwina’s short-lived affairs, his continued over many years, greatly upsetting her. ‘It was all right for her to have her own boyfriend, but she wasn’t so keen on my father having a girlfriend,’ remembered their daughter Patricia. ‘She suffered from this dreadful jealousy all her life and even when she didn’t want him herself, she still hated the thought of him with anyone else.’

The Mountbattens’ turbulent marriage began to flounder and by the late 1930s Edwina was spending most of her time partying, while Mountbatten was inventing strange contraptions including elasticated shoes and a ‘simplex’ shirt ‘that he could slide into like a stretch suit’. One of the only things they still had in common was their enthusiasm for collecting exotic pets, from chameleons to a Malayan honey bear nicknamed Rastus. The arrival of war thus provided the couple with a much-needed sense of purpose. Edwina volunteered at air-raid shel- ters while Mountbatten lived out his fantasies of wartime derring-do.

He wasn’t very good at it, but he did discover a fabulous talent for PR. After sinking his ship, the Kelly, he managed to transform his defeat into a story of such valour that the British government financed an entire film about it. The Ministry of Information briefly protested that a film about sinking a British ship would damage wartime morale but was forced to renew its support after Mountbatten personally peti- tioned his cousin, the king. A young Richard Attenborough was cast to debut in the film, entitled In Which We Serve, and the fraught produc- tion ended up being nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars, only losing to Casablanca.

Still, when Churchill and Roosevelt appointed Mountbatten as Supreme Allied Commander of South East Asian Command (SEAC), the military regarded him more or less as a joke. ‘Seldom has a Supreme Commander been more deficient of the main attributes of a Supreme Commander than Dickie Mountbatten,’ concluded the head of the British Army. US general Joseph Stilwell agreed, describing Mountbatten as nothing but a ‘glamour boy’ with ‘nice eyelashes’, while his soldiers joked that SEAC stood for ‘Save England’s Asian Colonies’ or ‘Supreme Example of Allied Confusion’. However, Mountbatten himself was thrilled with his new appointment in India, and thought it might even help his ailing marriage. ‘I really don’t know how I will be able to do this job without you,’ he wrote to Edwina. ‘Wouldn’t it be romantic to live together in the place we got engaged in.’ But she was engrossed in an affair with a British officer, Bunny Phillips, and declined her husband’s offer. Mountbatten worried he might have to file for divorce, and set off for Delhi alone.

Once in India, he initially did little to dispel his ‘glamour boy’ image. In a mirroring of Dorman-Smith fleeing Burma with his pet monkey, Mountbatten arrived on the front line trailed by a personal barber and his pet mongoose Rikki Tikki. Misfortune awaited the poor animal: the morning before a visit to the 4th West Kent Regiment, Mountbatten’s steward accidentally stepped on Rikki Tikki, killing her. ‘Poor Moore was quite white from the shock of having been the cause of her death,’ wrote Mountbatten. But despite the ‘terrible tragedy’, the new commander utterly inspired the West Kents. One lance corporal noted with amazement how this polished aristocrat who ‘looked like a movie star’ was in fact very down to earth, and another jotted in the regiment war diary that ‘morale was raised as if by magic’.

Soon after, Mountbatten moved SEAC headquarters to the Kandy botanical gardens in Ceylon. He designed his new organisation a logo and set up his own radio station, Radio SEAC, which beamed news of the war to soldiers from Aden to Japan. Then he began preparations to turn the tide of war against the Japanese.

Sam Dalrymple is a Delhi-raised Scottish historian and award-winning filmmaker. He graduated from Oxford University as a Persian and Sanskrit scholar, and also studied at the University of Isfahan and Ferdowsi University of Mashhad in Iran. He has worked across South and Central Asia, including stints with Turquoise Mountain in Kabul, and with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture in Hunza and Lahore. To read more of Sam, visit https://samdalrymple.com/