Last week’s post posited that an invasion of Egypt by a military force from Mesopotamia's Uruk city-state (in Sumer) was pivotal in forming Pharaonic Egypt, driven by trade demands between the Indus-Sarasvati region and Sumer. The notion of a Uruk invasion has sparked debate over the 20th and 21st centuries — initially widely accepted, then challenged post-1945 by a politically-correct focus on Egypt's indigenous development, and recently facing renewed scrutiny. Here’s a concise overview of the arguments.

Archaeological Evidence for External Influence

Flinders Petrie, a foundational figure in archaeology, conducted excavations at Naqada, Egypt in the 1890s, uncovering approximately 200 graves that revealed two distinct burial practices. Native Egyptians were interred in simple pits covered with palm leaves, while another group was buried in mud-brick-lined tombs, a style characteristic of Sumer in Mesopotamia and northwest India’s Indus-Sarasvati civilisation. These brick-lined graves contained Sumerian-style pottery adorned with images of boats and figures wearing feathered headdresses, alongside Egypt’s first cylinder seals— associated with trade between Sumer and the Indus-Sarasvati region. Lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone sourced from the north of that region and traded through Sumer.

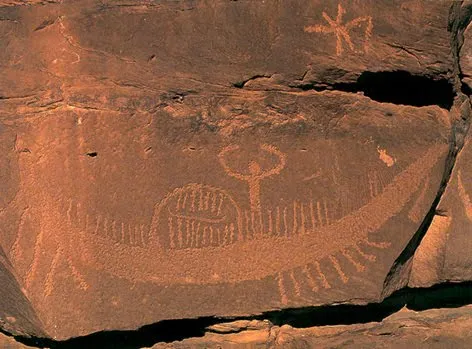

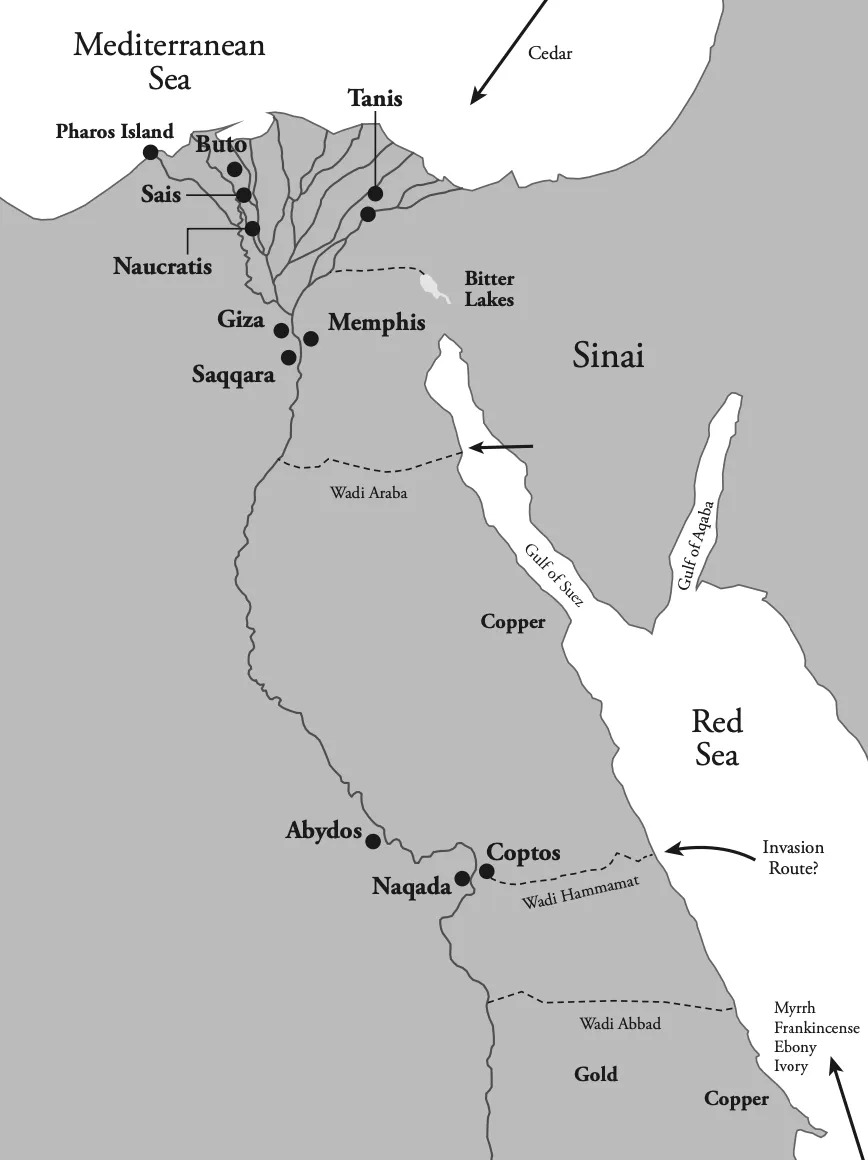

Further evidence supported these connections. Architectural features with recessed and projecting designs, typical of Uruk’s monumental structures at Abydos and Naqada, and later at Saqqara after Egypt’s unification. An ivory-handled flint-bladed knife from this period depicts a figure in Sumerian-style attire wielding a pear-shaped mace, a “master of the beasts” motif, alongside scenes of a land and naval battle. In these scenes, short-haired figures in Sumerian-style boats, accompanied by Sumerian-like dogs, defeat long-haired opponents in Nile-like vessels. Petrie therefore proposed an invasion from Uruk to establish Egypt’s first Pharaohs: a momentous event. Petroglyphs discovered in the 1930s along Red Sea wadis, depicting similar boats, figures with feathered headdresses, and pear-shaped maces, suggested further proof and the invasion route from the Red Sea. It was called ‘The Dynastic Race Theory’ and was widely accepted.

Post-War Historiographical Shifts- Political Correctness

The Dynastic Race Theory fell out of favour after World War II due to three major developments. First, the Holocaust, which claimed at least five million lives, primarily Jews, rendered racialised historical narratives politically sensitive.

Second, decolonisation prompted newly independent nations to craft histories celebrating their cultural autonomy. As historian John Darwin observes, these nations sought narratives that “placed their own progress at the heart of the story.” This led to a preference for theories attributing Pharaonic culture to indigenous development, with Uruk’s influence reframed as the result of trade rather than invasion or migration.

Third, specialist Egyptologists and Mesopotamian scholars, protective of their fields’ distinctiveness, often resisted interdisciplinary connections. For instance, despite the discovery of Khufu’s boat in 1954 next to his pyramid and the Abydos boats in the 1990s, resembling those of the wadi petroglyphs, most Egyptologists noted these findings without exploring their implications. Similarly, the abrupt appearance of hieroglyphs in Egypt, with no evidence of gradual development despite the region’s dry climate (ideal for preserving such records), contrasts with the well-documented evolution of cuneiform in Sumer.

Challenging the Consensus: Evidence of Cultural Exchange

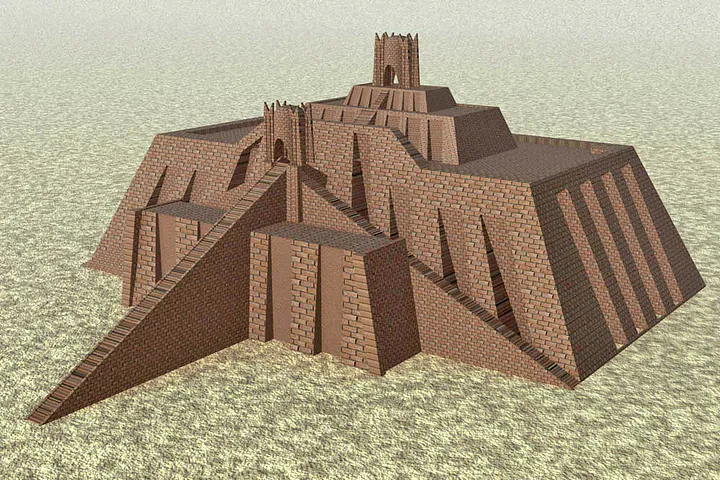

Generalist historians and polymaths have sought to revert to the pre-war consensus. Peter James highlighted similarities in architecture, pottery, and military standards between Egypt and Sumer, noting the use of imported materials like lapis lazuli, gold, and Lebanese cedar in Egyptian temples and graves—materials previously associated with Sumerian imports. Jared Diamond questioned the absence of proto-hieroglyphic evidence in Egypt, suggesting that Egypt’s dry climate would have preserved such records if they existed, unlike the evidence of gradual development of cuneiform in Sumer. The Narmer Palette, housed in Cairo’s National Museum, depicts a king wielding a pear-shaped mace, poised to strike a prisoner, alongside Sumerian-style mythical beasts and a bull symbolising royal power, a motif common in Sumerian iconography. Egypt’s first pyramid was Djoser’s, a step-pyramid resembling Sumerian ziggurats. The creation myth of Nun (Egypt) and Nunki (Sumer) is similar and Sumer’s Seven Sages ‘myth’ who brought civilisation is copied in Egypt’s founding story.

They challenged the narrative of purely indigenous development. While trade alone could explain some influences, the scale, specificity, and suddenness of these cultural innovations, especially deep religious and philosophical ideas cannot be brought just by trading influences. When I first visited Cairo’s National Museum, I was struck that Egypt’s predynastic exhibits show no hint of the revolution to come.

The Role of Maritime Trade and India’s Influence

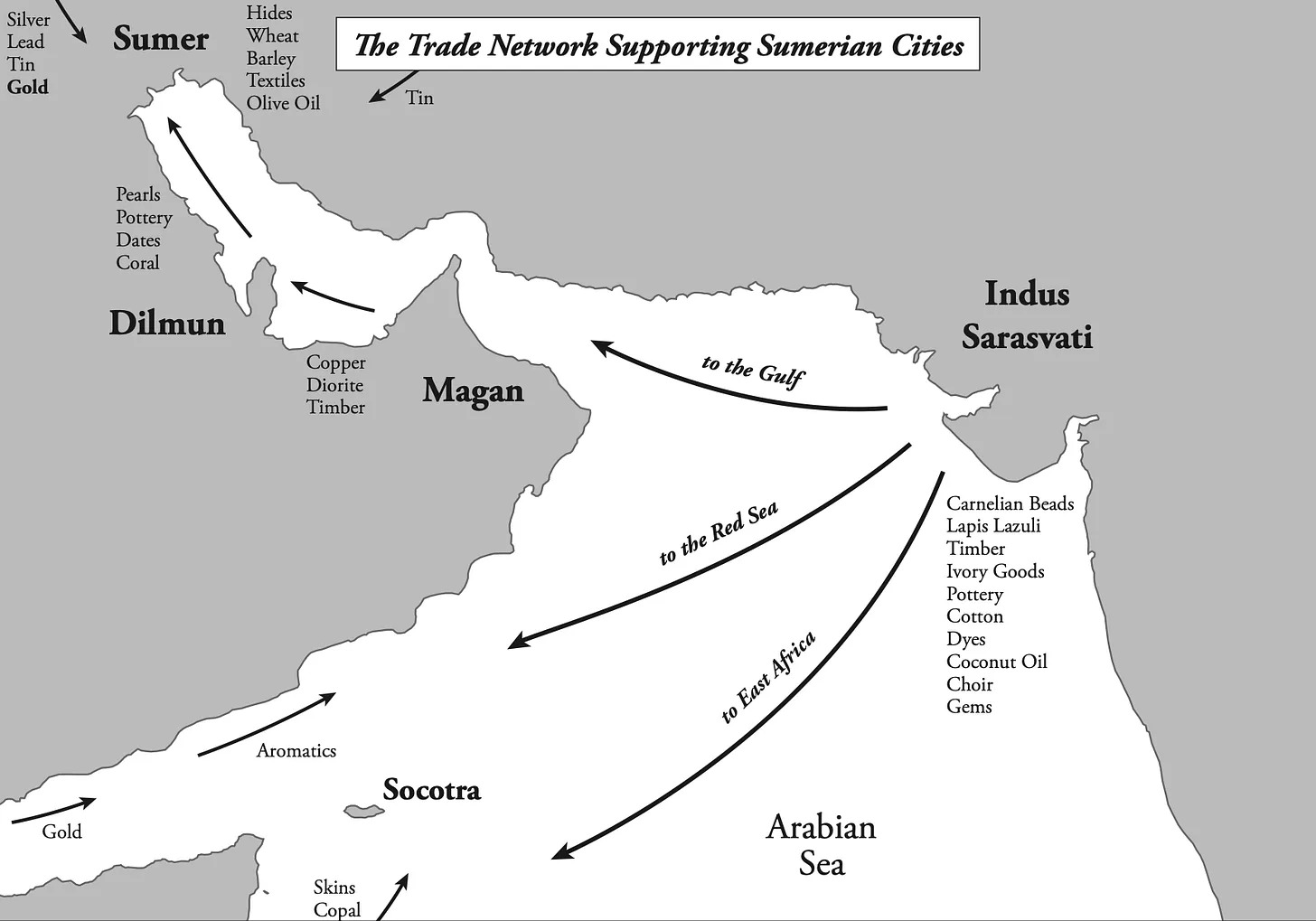

Why might Uruk have invaded Egypt? Last week I suggested an answer. Examining the ancient Indus-Sarasvati-Sumer trade network, something I don’t believe others have done, suggests the Indus-Sarasvati civilisation supplied arid Sumer with voluminous imports, including foodstuffs, timber, cotton, spices, locally manufactured gold, carnelian and agate beads, lapis lazuli, etc., as well as east African products. To sustain this considerable trade, Sumer’s woollen textiles would not have been adequate. But Uruk’s colonies further north and outposts in Anatolian sold cloth for silver, tin, lead and gold, some of which India would have wanted. Increasing Sumerian imports however, needed more metals, especially gold, loved by Indian civilisations throughout history. Egypt’s lack of centralised power, the Nile Valley and its abundant gold were strong incentives to source it directly. Coordination with Phoenician traders in the Levant, who supplied cedar, previously supplied to Sumer, and other Mediterranean products, facilitated this network.

Historical Bias and India’s Marginalisation

The Indus-Sarasvati civilisation’s huge economic power in the wider trade network has been obscured by modern, well-meaning post-war political correctness prioritising national narratives. The misguided “Aryan Invasion” theory and an inaccurate Mediterranean Bronze Age chronology (I will return to this in due course) have similarly marginalised India’s role. Hopefully, the huge economic power of the Indus-Sarasvati civilisation is now beginning to be realised. Further details can be found in How Maritime Trade and the Indian Subcontinent Shaped the World You can read the first chapter on Substack here

Article republished from Nick Collin’s Substack. Visit maritimetradehistory.com to find out more about the author, book, and where to buy.