The world of Short-Form content is an interesting place. Upon the Indian Government’s decision to ban TikTok in the country, swathes of netizens amassed unto the Reels page of Instagram, where we - and the world - got to see Indian culture, comedy and news, live on Zuckerberg’s “World Stage” - and, as an Indian American (following the U.S. Government’s decision to ban the app for 18 full hours) - I have a vested vehemence against TikTok, which I have never used. Living in the age of short-form content online, I relied on Instagram Reels instead as a source of doomscrolling dopamine.

I’ve often struggled to grapple with Reels, viewing the hyper-fast editing and vlogging as a grim realization of the infamous “15 minutes of fame” quote used to describe the early stages of the internet. Today, everyone wants to be an influencer, everyone wants to look cool on a world stage, and everyone is attempting increasingly esoteric strategies to achieve the same. This especially worries me, as one trend is singularly visible throughout the Indian space of online video creation - a haunting proclivity that reveals a simple truth: in our unintended - but real - phenomenon of joining global platforms, we are corrupting and irreversibly damaging our mother tongues, and how they will be remembered and learned by our progeny.

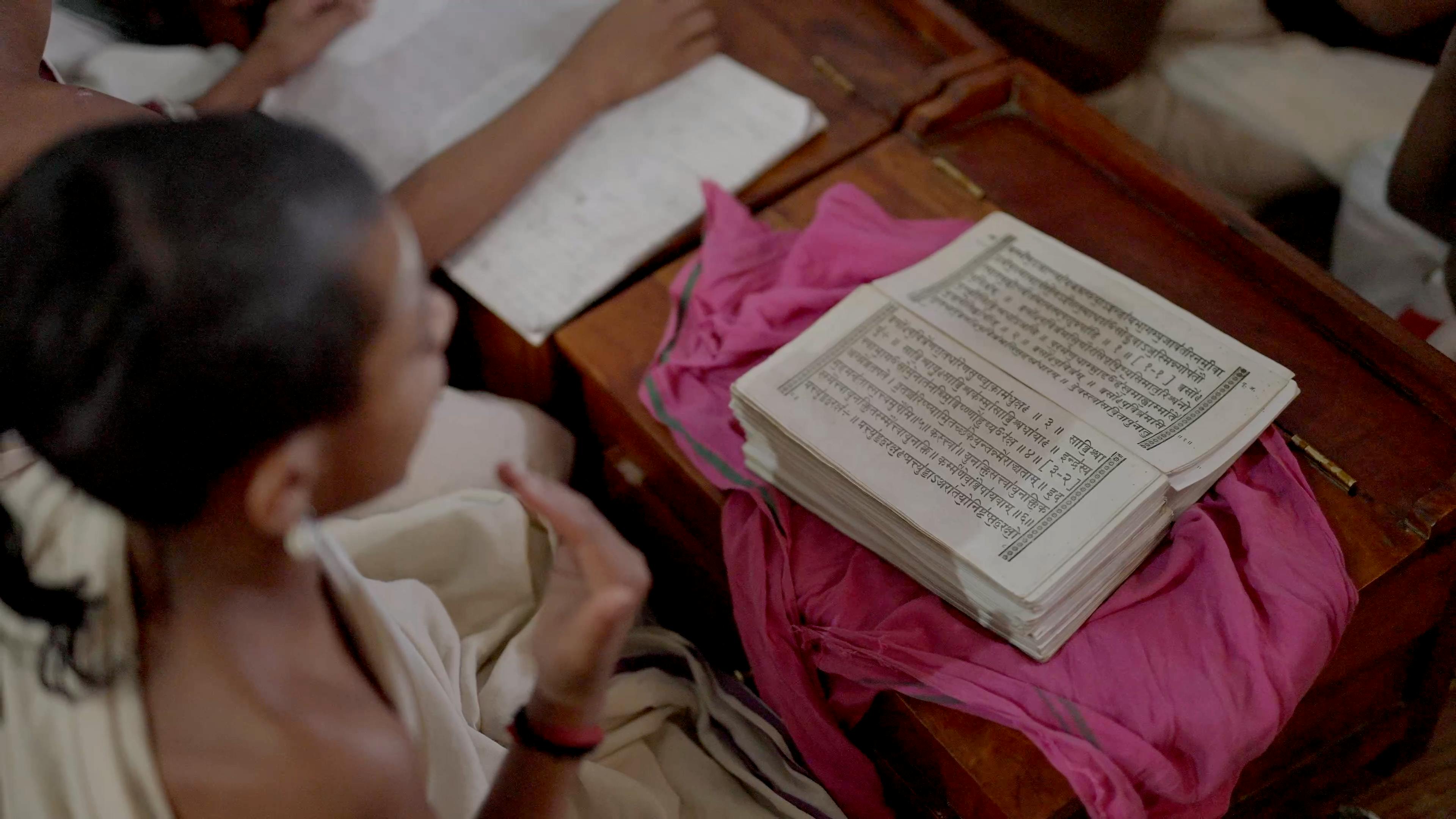

I learn languages as a hobby, and so far in my life have gained a decent proficiency in the four major South Indian languages - Malayalam, Tamil, Kannada and Telugu - alongside Hindi. If for nothing else, these languages are nearly universally recognized as ancient, with some languages having thousands of years of spoken history. Sanskrit and Tamil, for example, have been continuously spoken since at least 3,000 BC, and some estimates put Sanskrit’s origin as old as 7,000 BC as well. There is such a rich history of the births and evolutions of languages across India as well - Brahmi inscriptions theorized to reach Tamil Nadu from Jharkhand, which got there from Harappa; the evolution of Devanagari, Telugu-Kannada, Bengali and Vatezhutthu, the Sanskritification of South Indian languages through Maharashtrian Prakrit and Sanskrit itself - the list goes on and on and on. What is undeniable is how uniquely beautiful these languages are. The phonology of Indian languages is so unmistakably sonorous that Portuguese explorer Niccolo de Conti famously did not know whether the denizens of Visakhapatnam were talking or singing.

Yet where have we come today? Our understanding of our own native languages is at an all-time low - and, as more and more Indians join the global diaspora, we forget our language to a greater, more extreme degree. Take, for example, subject names: Any English medium Indian student (Vidhyārthi) no longer knows the names of things that their own parents and grandparents thought was common knowledge. Diaspora children, far less. I can not tell you how many Indian-origin students I have met on college campuses who meekly answered “I can understand it …” to the question of “oh, you’re [Native Language] - can you speak it?”. Undoubtedly, I have my own motives: I wish to speak with them in their native tongue so I can practice the languages I’ve been learning. But I am continuously appalled by how few of them seem to speak their language, and how fewer still seem to care that they don’t.

This is especially interesting in American academia, which has been consumed by the identity politics movement of the 2010s to a rather unsustainable degree. In my city of Minneapolis, the beginnings of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 seem to not matter to people who are consciously aware that they are disconnected from one of the major aspects of their culture. Friends and connections in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom have only corroborated my worries, and the rapid urbanization of India leaves her vulnerable to the same issues. I vividly recall an account from a close friend who visited Whitefield, Bengaluru on a family trip, and was shocked to notice that his younger cousins - all between six and fourteen - did not speak a single word of Telugu (their native language) or Kannada (Bengaluru’s language). In fact, with the recent transition of government schools in Andhra to the English medium, only 5% of schoolchildren this decade are estimated to learn their subjects in Telugu.

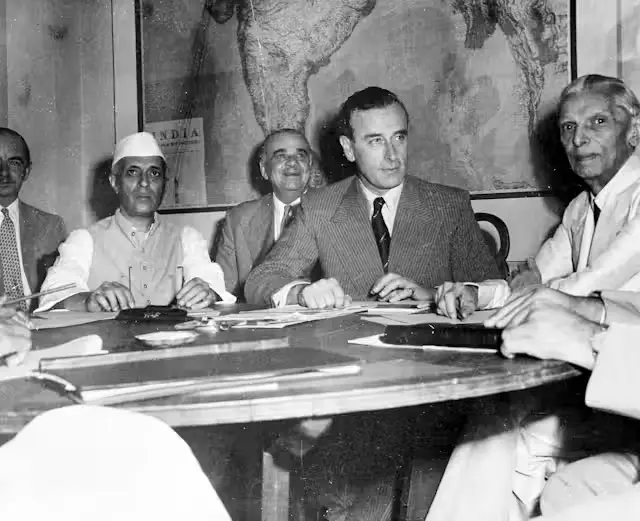

And what has transpired in India? We are at war with ourselves on a linguistic front. Draconian language restriction laws in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have stigmatized a “North-South” language divide that never existed in the first place. The only thing that separates North and South India - linguistically - are a few grammatical structures that change how sentences are formed. In reality, even Tamil has not escaped the warm, loving embrace of Sanskrit phonology, and we all, in part, speak the language of God when we speak our native languages today. Whether we live in Gujarat or Bengal, Kashmir or Tamil Nadu, a child of Sanskrit is a child of the Gods themselves, and our belligerent nature to divide ourselves into what makes these languages different (spoiler: it’s not a lot!) fuels our psychological discontent to learn our languages better. Obedient to this, are we embracing an Anglification? Out of what? And for what apparent reason?

For those who don’t see these silly political games, and actually speak the language, in continuum, there is a much larger issue. At our earliest convenience, we take any word that could be (for even a split second) thought of in our native tongue and replace it with an English loanword. Our languages have been reduced - rather pitifully - to the utilization of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian grammatical structures to loop together English words. Notwithstanding complex words for normal people, such as the Sanskrit word for Economics (Arthaśāstra), reflected in most languages as the same word for the same meaning, even the simplest words have become victims of Anglification. Somewhere along the line, Prayatn became try, Prārambh became first-first, and learning the script of a language - especially for diasporan children - became a burden and not a symbol of pride.

I believe firmly that it is imperative to restore a sense of pride in our language and divest it from all its non-Indic influences. For a country that so uniquely hates the British because of their Colonial-era subjugation of Indians, why are we allowing our languages to get colonized to such a heartbreaking degree? For a country that is ready to chant Vandē Mātaram, or professing love to the Motherland, where is the professment of love to the Mātṛbhāsh? And for a country that claims Unity in Diversity, why are we monotonizing our native languages?

Inspired by this notion, I am building Bhāsha, a company aimed to promote Indian language learning. But as a corporation, I can only provide a service - not the impetus for a cultural and foundational shift in changing how we as Indians view what are undeniably the most advanced, developed, and singularly beautiful languages on Earth. No, the issue runs far deeper. We must collectively call on our governments to further advocate for, and build infrastructure supporting the development, preservation and longevity of our native languages. We are among the most linguistically diverse places known to mankind’s history, but the eternal Indian philtosophy of Unity in Diversity can only be fully realized when we can preserve those diverse linguistic voices for our future generations. One day, I hope we can then bring this sentiment to our online presence - Instagram Reels and YouTube Shorts abound, in the native languages our ancestors fought so hard to preserve. Tasked with a similar struggle, we can rise up to the challenge and build - collectively - a foundation for languages in India that will withstand any test of time.